Japanese traditional woodblock print is characterized by the collaboration with e-shi (paint artist), hori-shi (who carve woodblock), suri-shi (who print ukiyo-e) and hanmoto (who publish woodblock prints). And the art work is completed by the dynamic expression of knowledges, techniques and spirits of those artisans on a washi paper. In general, Japanese traditional woodblock prints are famous for the ukiyo-e in the Edo period and "Shin-hanga" (means, new print) in the Taishō or early Shōwa era, and the Meiji period is seemed as a decline period. Certainly, the market of ukiyo-e had been replaced by western new technology and declined. The style of painting also became incompatible with the times. Especially, after the Meiji 20s, the number of new art work had decreased sharply and ukiyo-e had just turned to the end.

But each artisans of this traditional woodblock print had showed a new movement to survive and correspond to the rough wave of the era. With trial and error, e-shi had fused with the modern Japanese art circles that was in the process of developing and hori-shi and suri-shi had developed the techniques that made elaborate re-production of hand-paintings or old painting possible in a different way than before. These movement had been done in a new stage unique to the Meiji era, such as illustrations of newspapers, kuchi-e of modern literatures, art magazines like “Kokka” or “Bijutu Sekai” (means, world of art), exhibitions and so on. And, while the decreased hanmoto was forcusing on the re-print of Edo ukiyo-e, some hanmoto such as “Daikokuya Matuki Hēkichi” or “Kokkeidō Akiyama Buemon” had created excellent modern ukiyo-e prints by these new movements with Mizuno Toshikata, Ogata Gekkō or so on.

Moreover, these flow had been matured in some art works from the end of Meiji to Taishō period. They were born with the developed techniques by Kokka or woodblock prints and expressed the charm of Japanese hand-paintings that were different from the ukiyo-e before in the points of gradation of colors, blurring of handwriting or so on. As Japanese art, they gained a high reputation overseas. While the “Shin-hanga” that followed next expressed the techniques of suri and hori such as leaving the trace of baren (a tool to transfer ink or pigments from a printing plate to paper by rubbing the back of the paper) or leaving a blur peculiar to prints and produced an art of woodblock printing differ from hand-drawing, these works put the emphasis on the expression of the painter's hand-drawing to the utmost, the transcendental skills of curving and printing were not asserted on the surface, and they were quietly integrated into the expression of the e-shi.

Because these art works were created in a short term, the number of them were few, and the production were focused on overseas, they had been hidden behind the big flow of “Shin-hanga” and became works that were not known commonly in Japan. In this section, we introduce “Nōgaku Hyaku-ban” (means, one hundred Noh scenes) by Tsukioka Kōgyo and kacho-ga (print/drawing of flowers, birds or living things except human being) by Ohara Koson especially as ones of them. These art works include enough artistic quality to prove that the crystals each artisans had developed on a new stage for survival had been reached another arrival point different from “Shin-hanga”. And they appeal us that the traditional woodblock prints in the later Meiji era, between the Edo ukiyo-e and Shin-hanga, should not be simplified as “declined” or “ended” at that time.

- Tsukioka Kōgyo Meiji 2nd - Shōwa 2nd (1869-1927) Open or Close

Kōgyo was born in Tokyo, studied drawing on pottery by his uncle when he was 12 and studied nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) by Yūki Masaaki at Tokyo-hu Ga-gaku Denshū Jo (art school). At age of 18, he began studying under Tsukioka Yoshitoshi who became his stepfather. After that, he also studied under Ogata Gekkō who was a nihon-ga-ka (Japanese-style painting artist) and ukiyo-e-shi. He aslo studied under Matumoto Hūko who was a nihon-ga-ka. He honed his skills in the environment reflecting the situation of the world of Japanese paintings in the early Meiji period. From Meiji 20s, he had started to send his works to exhibitions, received awards and played an active part in ukiyo-e, illustrations on “Hūzoku Gahō” or so on. Meanwhile, the world of Noh had overcome the crisis after the Meiji Restoration that made it lost its sponsors and had worked actively to increase the number of customers, mainly wealthy customers, further.

Kōgyo began to be overwhelmed with Noh painting from around Meiji 30th and sent many Noh paintings to exhibitions. For 5 years from Meiji 30th, he created “Nōgaku Zu-e” made up of 261 woodblock prints (including table of contents). And from Taishō 11th to 14th, he created “Nōgaku Hyaku-ban” made up of 102 scenes, some are made up of double or triple prints, with 122 gorgeous woodblock prints (including table of contents). They are also known as his masterpieces.

While he gave weight to the research of Noh costumes, songs and stage sketches, he also said “Although Nōgaku painting should based on the rule of Noh, it should not stick to too much about details or sketches, because the reason I draw Noh is that I also strongly attracted by the elegance of Noh, itself.” (“Sho-ga Kottō Zasshi” magazine in the Oct. number, Taishō 1st) about Noh paintings. In addition to serving as a judge at Nihon Bijutu Kyōkai Ten (means, Japan Art Association Exhibition), he continued to exhibit at many exhibitions until the later years, and he played an active role as a specialist in Noh painting. It seemed that the number of works he created was over 1000 scenes, just counting woodblock prints.-

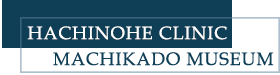

“Nōgaku Zu-e Shō-Jō” Meiji 31st (1898)

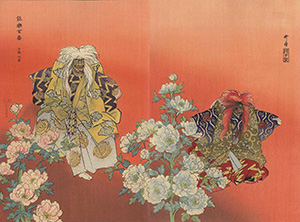

●Nōgaku Hyaku-ban

Taishō 11th ~14th (1922~1925)“Nōgaku Hyaku-ban” is a series made up of 100 scenes and 2 scenes of tables of contents with 122 woodblock prints. Is was published 3 prints for a month by the same hanmoto (who publish woodblock prints) “Daikokuya Matuki Hēkichi” as “Nōgaku Zu-e” was published by. They are gorgeous woodblock prints with high quality hōsho-shi papers and several tens of times of suri that re-express not only his brushwork but also his color. Some were printed using gold and/or silver. This series is the best masterpiece by Noh painting artist Tsukioka Kōgyo who expressed the beauty of yūgen (mysterious, subtle and profound) of Noh by centering the Noh performers and saving the backgrounds. And this series is the biggest series published by “Daikokuya Matuki Hēkichi” with the techniques cultivated since the middle of Meiji, in the era of Shin-hanga.

-

“Hagoromo”

Taishō 11th -

“Ishi-bashi Sō-zu”

Taishō 11th -

“Okina-shiki Sansō-zu”

Taishō 12th -

“Arashiyama”

Taishō 12th -

“Hashi-benkei”

Taishō 12th -

“Kinsatu Nanto Maki-nō”

Taishō 12th -

“Atumori”

Taishō 13th -

“Semi-maru”

Taishō 13th -

“Mochizuki”

Taishō 13th -

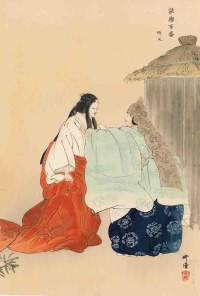

“Dōjōji”

Taishō 14th -

“Kurama-tengu”

Taishō 14th

-

-

Ohara Koson (Shōson/ Hōson) Meiji 10th - Shōwa 20th (1877-1945)

Open or Close

Ohara Koson was born in Kanazawa, Ishikawa prefecture. He began studying under Suzuki Kason who studied under Nakajima Kyōsai who studied under Kikuchi Yōsai in his teenage years. Kason was very good at Japanese-style painting and woodblock print, especially kachō-ga. He sent his works, mainly kachō-ga, to Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai Ten whose central figure was Okakura Tenshin or other exhibitions, received hornable mentions and went forward the path as a Japanese-style painter. And when kachō-ga by Watanabe Seitei or Suzuki Kason had already got popularity abroad, the kachō-ga by Koson caught the eyes of Ernest Francisco Fenollosa and he was led to produce woodblock prints for export.

Around Meiji 40th, it is seemed that he created over 300 kachō-ga for export, they got great popularity overseas, and he created kachō-ga mainly. From Taishō period, he changed gago (a pseudonym) as “Shōson” from “Koson” and created hand-paintings. From around the beginning of Shōwa period, he produced Shin-hanga under hanmoto Watanabe Shōzaburō and became one of the representatives of Shin-hanga. But the term he created Shin-hanga was short and he created slightly in his later years as “Hōson”. He is a remarkable person not only as the artist who fully expressed the beauty of Japan in kachō-ga but also as an great artist who created both of prints that expressed the beauty of hand-drawing that got the end after receiving the transformation of the Meiji traditional woodblock prints by “Daikokuya Matuki Hēkichi” and Shin-hanga that was created as rebirth of traditional woodblock prints by “Watanabe Shōzaburō”.

●Kachō-ga by Ohara Koson

Around Meiji 40th, Koson created kachō-ga that were published from “Kokkeidō Akiyama Buemon” and “Daikokuya Matuki Hēkichi” to export under the guidance of Ernest Francisco Fenollosa. It is seemed that he created over 300 mainly in the end of Meiji period. It is said that these kachō-ga were created by making paper drafts using photographs to transfer Koson’s hand-drawing original painting and curving woodblocks. They express the touch of brush like hand-drawing and delicate shades of colors brilliantly using the new techniques cultivated in the late Meiji period.

-

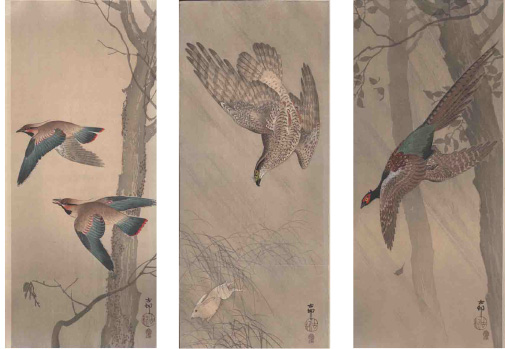

Published by “Kokkeidō Akiyama Buemon”

End of Meiji period -

Published by “Daikokuya Matuki Hēkichi the 5th”

End of Meiji period

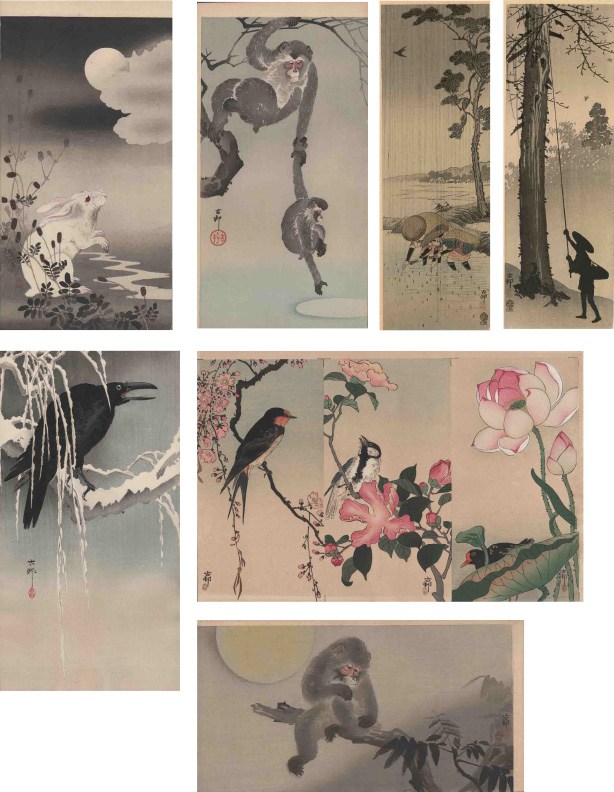

●Shin-hanga by Ohara Shōson

-

Published by “Watanabe Shōzaburō”

Beginning of Shōwa period

-